The Samurai: Myth and Reality

The Japanese warriors, known as samurai, have not yet finished inspiring the fantasies of multitudes of martial arts practitioners all over the world. Their culture, their combat techniques, and their way of thinking, are still presented as an example to follow in order to reach an ideal form in all the martial arts. Nevertheless, the reality is far removed from the popular image which relies on cliches whose facts have been watered down. This article discusses the reality of these warriors who are portrayed by pop history as being without fear and reproach, loyal to the death, having qualities that gained them the admiration of many.

Origins

First, the term samurai comes from the old Japanese saburafu, which signifies “to be in the service of”. At the beginning of the Heian period (794-1186) it applied to those who were in the service of the court nobles known as kuge, or of the emperor established in Kyoto, most notably women. They were the followers of the important men of the Japanese Nobility. Starting in the 9th century the word is more and more frequently associated with the notion of escort and designated, for a time, the servants of the nobility. Moreover, the term samurai, at its origin, does not bring us to the meaning of warrior. At the beginning of the Japanese middle ages there existed no standard word to designate men who specialised in combat. We see mention of words that imply the profession of weapons such as musha (man of arms) or mosa (ferocious). We also find the term gokenin which designates the vassal relationship which binds or honors the warrior.

According to the most reliable sources, the samurai formed the base of the provincial notables, and of the lower functionaries of the local administration belonging to the emperor. They had as their primary functions the creation and keeping of official documents, the gathering of taxes, the transport of funds to the capital, the maintenance of roads and public buildings, managing the police force, and the surveillance of cults and religious festivals. These local functionaries were leaders in agricultural exploitation and knew how to extract the greatest value from the land. They placed their manors in elevated positions and had a gathering of men whom they threw into the cultivation of flooded rice fields.

For operations that required heavy work like the digging of canals and reservoirs, the construction of low walls and dikes, and so forth, the master had acquired a certain prestige that allowed him to impose his authority on the peasants as well as on the small notables whom he considered as his own men. Little by little the master places his brothers or those close to him in strategic places throughout the territory after annexing new parcels. Small manors are constructed for them and satellite families are established who recognise the supremacy of the main branch, in charge of rendering worship to the ancestors of the clan. The head of the family was equally the head of a small band of warriors whom he lead into battle in defence of the domain and the manor. Therefore, the primary characteristic of this group of individuals united in the protection of the domain became progressively more militarised and transformed itself into a group of warriors during the period from the 9th to 11th centuries. It is in this way that the samurai came to be; they were both warriors and property owners. The samurai considered the lands annexed by their ancestors to be their domain and they themselves carried the name of the domain on which their manor was constructed, which was in close proximity to the sanctuary where they worshipped the protective deity of their clan as well as the tombs which venerated the souls of their ancestors. Losing this land was the epitome of dishonour.

The power of the samurai began to emerge in the 9th century as they started little by little to organise themselves into groups. The name of the arts which they practiced would also undergo several changes. In the 10th century we see tsuwamono no michi, the way of weapons, where the term tsuwamono designates the warrior or man of arms. We can also translate tsuwamono no michi as ‘the way of the warrior’. One century later the terms musha and mononofu came into use to designate the warriors, their methods of combat would have been known as musha no michi or mononofu no michi. The battles of the Heian period also give rise to the increasing use of the bow in conjunction with equitation and the term kyuba no michi (the way that consists of mastering the bow and equitation) is widely used. Beginning in this period the use of the word michi (the way) appears already to be an ethical preoccupation at the heart of various warrior groups. It was also during this Heian period that the first schools of kyu-jutsu (archery), such as the famous Ogasawara-ryu, were founded.

The sources which we have used, such as the Tale of Heiji and the Tale of Hogen, describe these warriors more often than not, as men covered in armour with a helmet, armed with a bow and a long sword, in command of several men who were self-professed experts of combat techniques and hunting. However, not any armed ruffian could be a samurai, even if they could be hired to guard the provincial administration buildings or to serve as hired hands in the domain. The samurai themselves were at the head of the domains and had to obtain nomination in order to serve the province in a military capacity; as an escort for tax collection convoys for example. They participated in the hunts offered by the governor of the province or organised the ceremonies for the comparison of ability in the practice of yabusame (archery on horseback against a stationary target).

Between 1051 and 1087, wars in the Tohoku region (in the north-east of Japan) opposed the samurai of Kanto (modern-day Kanto region) and Kansai (modern-day Kyoto area). Over the course of these tough battles close-knit relationships were forged among the samurai. Many among them sought to obtain fiefdoms in the recently annexed regions. In light of their failure against the local armies, there was a great deal of resentment towards the aristocracy and the kuge who were unable to withstand these attacks. At the same time, there appeared strong sentiments of pride in the man of arms, as well as in the values of heroism, loyalty, courage, fidelity to one’s general, and an unrelenting spirit throughout the samurai of the Kanto region, namely the Minamoto family. All of these notions were quite foreign to the court aristocracy.

One century later, between 1180 and 1185, two rival families: the Minamoto and the Taira, went against one another in what could be considered a civil war, after which the Minamoto emerged victorious. This hold on power by the warrior class would continue for another seven centuries; the Shogun was born.

The Culture and Philosophy of the Bushi

The way of horseback riding and archery, kyuba no michi, would be systematised into a way of the warrior that would much later become the famous Bushido. The samurai developed a culture that was totally unique. They constructed their political and cultural identity through violence and the waging of war. In this 'way of the warrior' there developed a complete disinterest in the material and in its place formed a great search for beauty and pure efficacy of movement. Honour and loyalty toward one’s lord, courage in combat, and prowess facing the enemy, became the motifs of warrior stories. From this point forward, the samurai considered themselves without rival in the arts of war, hunting, and horseback riding, something which they took great pride in.

The belief systems of their forefathers in the nobility of the imperial court, became replaced with a feeling of independence that was linked to the use of force, fury in battle, and to a new concept of honour. Riding on horseback, being armed, practicing the arts of war, and waging war, are the symbols that became characteristic of these former landowners turned warriors. They maintained ties of allegiance and dependence with their lord directly. The new vassal was simply presented by his lord before his other warriors. Following this ceremony the lord and his new man would drink together in public, from the same cup of sake, as a sign of their fraternity. Another characteristic trait shared by the warriors was individuality. The samurai was of course loyal, but he only followed his lord into battle if he was sure to be given a domain that was to his advantage. Gaining control over newly conquered land was what motivated the samurai to join a lord in battle. Combat was not accepted unless the samurai was properly compensated; courage for these warriors didn’t make any sense unless the enemy had riches for the taking.

Moreover, loyalty was a certain virtue only as long as it didn’t threaten the primary domain of the samurai. If not, treason – the changing of alliance in mid-combat – was money in the bank. Between the warrior tales and the family chronologies that describe the fidelity of vassals to their lords and the historical reality, there is a disparity that some, who are not familiar enough with medieval Japanese history, may have difficulty coming to terms with. For the most part, high ranking warriors and the most prominent historical figures, such as Hojo Ujiyasu (1515-1571), Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616), Takeda Shingen (1521-1573), Uesugi Kenshin (1530-1578), etc… all practiced treason and changing allegiances. These instances of political treason in no way tarnished the honor of the lineages to which their protagonists belonged, they were even rewarded by the victors of their respective battles.

The practice of combat techniques begins very early for the warrior, and starts first of all with a thorough study of the treatises on military strategy and espionage, known collectively as bugei shichisho. These treatises, numbering seven, contain all of the teachings necessary to conduct a battle in the broad sense, how to read into enemy strategies, how to carry out an attack, the study of topography, meteorology, astronomy, etc.

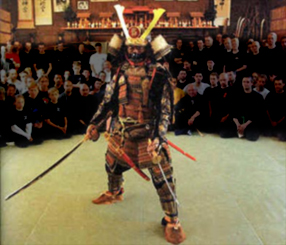

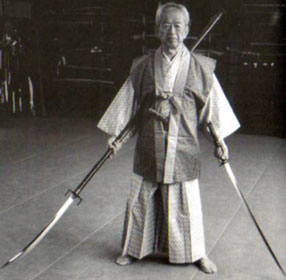

Parallel to the study of these treatises, was the practice of the various disciplines of combat, such as the art of the spear, halberd, bow and arrow, equitation, kenjutsu, iai-jutsu, jujutsu, and so forth, numbering eighteen in total and known as the bugei juhappan, or the eighteen warrior disciplines. The first bujutsu schools to which the warriors devoted themselves were founded for the most part, according to reliable sources, in the Muromachi period (1333-1467). Naturally, a number of schools take pleasure in relating that their founding dates back even earlier. Nonetheless, the official texts show that the schools of which we are sure today were founded in the Muromachi period. Three such schools form the three currents of bujutsu which would later influence a large number of arts, most notably in the Edo period (1603-1868). These consist of the Kashima no tachi, that groups the Tenshin shoden Katori shinto-ryu of Izasa Choisai (1386-1488), the Kashima shinkage-ryu of Matsumoto Bizen no kami (1467-1524), and the Shinto-ryu of Tsukahara Bokuden (1490-1571). This lineage goes by the name shinto-ryu. The second lineage is the Nen-ryu founded by the monk Jion Nenami (1350-?), and third lineage is the Kage-ryu founded by Aisu Ikosai (1452-1538). These three lineages have as their common core: the use of several weapons of varying length, for example the art of the spear and of the long sword in yoroi uchi-tachi, which is combat in armour. They developed many subtleties in the art of using the body as a result of using armour on the battle field. Their founders were all high ranking warriors and themselves belonged to prominent warrior families. The difference for these men rests in the fact that they did not die by committing seppuku or hara-kiri, but rather finished their lives transmitting their science to the subsequent generation.

We must also not forget the philosophy of Zen Buddhism and Mikkyo (esoteric Buddhism), that played a role in the daily lives of a large number of samurai. Some, who were more spiritually devout than others, practiced their combat techniques in conjunction with spirituality. The practice of Sado (the tea ceremony), calligraphy, painting, and ‘No’ theatre, were also disciplines that allowed these warriors to polish their spirits as well as discover new horizons for them to apply the practice of martial arts. We can say categorically that this 'spirit' of the samurai would go on to influence Japanese culture for seven centuries and would enrich numerous aspects of this culture.

Another aspect of the philosophy and rituals of the samurai that has attracted a lot of attention is seppuku, also known as the more vulgar hara-kiri. This was the ritual suicide that the samurai performed to save his honour. At least this is the more common definition. In fact, the systematisation of this ritual came later, and sources show that only warriors of high rank practiced this ritual. We have to wait until the middle of the Edo period for this ritual to be arranged systematically, such as when a lord would die, his entire court had to follow him in death. This ritual along with the Bushido code was used several centuries later by the propaganda machine of the nationalist army to galvanise the troops during the Second World War.

A Major Shift

Hideyoshi, the second unifier of Japan after Oda Nobunaga, attempted to subdue the warriors, to create a kind of absolute monarchy, as well as to disarm the peasantry. With all of the reforms put into place by Hideyoshi, there was no access to the warrior class other than by birth. The samurai would, from now on, make up the upper layer of society, above the peasants, artisans, and merchants. However, it was under the Tokugawa, with the establishment of peace during the Edo period (1603-1868), that the samurai would transform little by little into a bureaucracy that was for the most part educated and competent. In times of peace, forced by their lords, they settled themselves in towns at the foot of castles where they would carry out tasks of supervision and administration which provided financial compensation. For the more skilled among them, the position of instructor of combat techniques was the most coveted. Some, like Yagyu Munenori, rose to the summits of the hierarchy, as in addition to his function as instructor to the family of the Tokugawa Shogun and his primary vassals, he also received the title of So-metsuke, chief of the espionage and surveillance network of the shogun. Therefore, it was possible for samurai of exceptional competence to acquire posts, though this was a unique case.

The transformation of the samurai during the years 1570-1620, from specialists competent in war and combat in all its forms, to specialists in administration was without a doubt a crucial moment in the history of Japanese martial arts and of Japan. This shift did not prevent the samurai from continuing to associate themselves with the way of the warrior, all the while continuing their study of the different disciplines of combat. However, it was at the beginning of the 18th century that the 'way of the warrior', the famous Bushido, would be transfigured into a sort of warrior ethic in a time when the samurai already no longer existed.

Many did not have the necessary competencies to become a bureaucrat in the service of the Shogun, or were simply unable to adapt themselves to the changes. A large majority of them fell into banditry, rediscovered work on the land, rented their services out, or opened a dojo. The resurgence of dojo and even the creation of schools of bujutsu were at there peak in the middle of the Edo period. During this time we witness a kind of democratising in the practice of the martial arts which used to be an exclusive privilege of the elite warrior. As a result, the editing of costly diplomas, more refined techniques, and the writing of increasingly detailed manuscripts, and so on, experienced a rapid growth. Additionally there was a shift from a qualitative transmission intended for a sole successor to mass instruction.

At the beginning of 1850, with the Western threat making itself more and more pressing, Japan was forced to open up its autocracy. A number of warriors favourably acquired techniques from the Western world, whereas for others, such as for those who held power, Western ways fell on deaf ears. For these dissident warriors, modernisation and opening up to the know-how of Europe and America that would lead to brilliant careers founded not on rank but on merit, appeared to be a revolutionary means to completely strip themselves of the very power that was already slipping away. This lead to several battles between those in favour of opening up to the west and imperial rule and those apposed to these changes, instead supporting the old ways, loyal to the family of the Tokugawa Shogun. The loss of the latter would give birth to the Meiji restoration in 1868. All social classes were abolished and the samurai were stripped of their status, including the privilege to carry the two swords and keep their hairstyle. This is the period that the film The Last Samurai with Tom Cruise depicts.

Those who proved unable to adapt, refused the progress and attached themselves to other dissidents among whom the most famous was Saigo Takamori (1827-1877) who died by succeeding to perform the ritual of seppuku after losing a battle against the new imperial army. An unequal battle fought between obsolete weapons and tactics against heavy armament that was new to Japan. Those who were able to adapt themselves became high level state employees, specialists, or even capitalists. They no longer had the need to identify themselves with the old warrior regime. They established themselves, without too much trouble, alongside the bourgeoisie and the rich peasants in this new society.

The Samurai Today

It is difficult to say that today there still exist samurai in the literal sense of the word, that is to say a person in the service of a domain who, in addition to working the land and other functions, also practices the use of weaponry to protect his domain and family.

Today, people believe that the samurai was a kind of avenger or defender of widows and orphans, married to a single woman. However, the reality was for from this; by the beginning of the Edo period (1603) the vast majority of low ranking samurai, of which there were legions, were reputed for their rudeness, illiteracy, and asserted their samurai status by killing anyone who dared insult them. There are numerous historical chronicles and anecdotes documenting the extortions and other crimes perpetrated by these warriors.

So what does it mean to be a samurai today? Within this question is the idea of wanting to live in the past, an idea which goes against the basic principle that is at the heart of the creation and evolution of the samurai and of Japanese martial arts; the principles of adaptability and survival. It is in this context which we must understand one of the phrases from the Hagakure “the way of the warrior consists of meeting his own death”. This phrase can be interpreted in several ways, including ‘the death of the ego’. The first meaning remains without equivocation, that of survival, the survival of the clan, of the name, of the domain. In other words, not give in to death in order to continue fighting. That is the cost of preservation. This is the spirit of renunciation, of perseverance, of the desire to practice with, and learn from certain high ranking warriors and founders of schools, this is still present in the apprenticeship of combat techniques that are transmitted in Japan today.

Each period of world history as well as our own personal history brings its own lot of change. We can easily say that there still exist men who practice the same combat techniques created by these warriors and try to maintain a traditional form of the art of moving, as well as try to understand the world through a way where one seeks to move towards perfection or an ideal, similar to the samurai of old but with different objectives. Therefore, regardless of the practice or the period, the essential element resides in the spirit and application of this state of being in the present moment.

This is an edited version of an original text published by Kacem Zoughari in Kuden online magazine in May 2009

Next Article: The Budo of Change.